Our methodology obsession

The primary, and sometimes only, focus of most engineering organizations is product throughput. Typically the leading questions from executives are “when can we start?” and “how long will it take?”. We breakdown deliverables into smaller work streams that form a backlog of work that we can prioritize. Next comes the inevitable decision on whether we’re using Scrum or Kanban as the methodology to deliver this project, most often we convince ourselves the best approach is a mixture of the two; Scrumban. Once this important decision is agreed, arrived at either by the organization touted winner or by simply adopting what we are familiar with, we kick off with a planning session and the usual ritual of running on the feature treadmill until an arbitrary point in time where we have a retrospective and start over again. With the adoption of process we can now officially attribute ourselves “Agile”. Brilliant. But what have we gained here? What are the metrics that show me we’ve actually made any improvement? How do I even attempt to measure this? How do I translate the benefits into customer or business value? We’re blindly promised the world, a silver bullet and “Agile” is our panacea. Here’s an example of such evangelizing. An exert from a book titled “Learning Agile”:

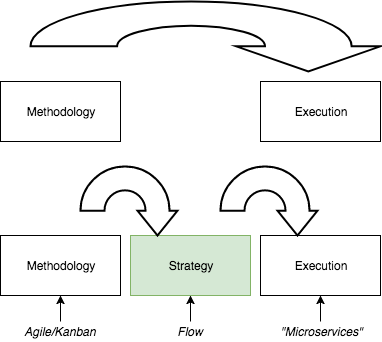

Just….wow. There is, of course, nothing wrong with Agile, Kanban or any other methodologies in themselves. The principles and values guide a way of thinking about software development, the antithesis of the early days of our craft. Aka “waterfall”. Who could argue with "Working software is the primary measure of progress” or "Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software”? The fundamental problem is that this focus is devoid of a real strategy to execute. They were never meant to be. They’re principles. Too many organizations are focussed on conforming to a methodology and in particular the rituals that support them. The leap to execution continues to emphasize our obsession with timelines and so we strive for predictability and optimize for inflexibility and invariance. On the face of it this approach seems logical because any flexibility or variance has the potential to add delay and we threaten our timelines. Those accustomed to the wrath of a delayed timeline have become savvy to the process and so we game the system in all future projects with the inevitable “padding” of timelines. The more granular our planning of timelines, the more padding we add and the less meaningful our estimates become.

A focus on “Flow"

A focus on timelines results, ultimately, in longer cycle times. Instead if we shift our focus to managing queues we can emphasize and optimize flow and reduce cycle times and cost of delay. The diagram below shows where flow fits in to the picture as an intermediary and strategy between methodology and execution.

But what exactly do we mean by “Flow” and how do we influence it? At a basic level we can derive similarities from manufacturing and specifically Lean Manufacturing, with it’s roots in the Toyota Production System (TPS). The study of work flowing through a system and in-depth analysis of queue theory. In my opinion, though interesting, I don’t think we even need to go this deep to emphasize the importance of Flow and we can make huge gains at a basic level. Software engineering can learn a lot from the Manufacturing industry but it’s important to remember there are some big differences in the repeatability, complexity and variability of tasks in software development. It is not like for like. For an in-depth understanding of Flow, I highly recommend the Book “The Principles of Product Development Flow” by Donald G. Reinertsen. As a taster to Reinertsens “Problems with the current orthodoxy” he states 12 problems that become the focus of the book:

- Failure to Correctly Quantify Economics

- Blindness to Queues

- Worship of Efficiency

- Hostility to Variability

- Worship of Conformance

- Institutionalization of Large Batch Sizes

- Underutilization of Cadence

- Managing Timelines instead of Queues

- Absence of WIP Constraints

- Inflexibility

- Noneconomic Flow Control

- Centralized Control

Instead of diving into each of these I want to reference some of these problems and provide real-world actionable examples of how we can use Flow as a focus to build high performing engineering organizations so that we can bridge the gap between methodology and execution.

Alignment through Foundational Systems and Standards

At the core of increasing flow in engineering organizations is a battle between centralized control, which favors alignment, and decentralized control which favors autonomy. The goal is that we achieve both but an approach to side with autonomy and an underpinning of minimum viable standards helps us achieve both. As an example, let’s look at logging. There’s value in us defining a logging standard that all teams should conform to. In the case of an outage or degradation of service we can reduce the cognitive load on Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) teams that may be in place to triage issues. By aligning on “timestamp” instead of “time-stamp”, as a trivial example, we can reduce the triage time which increases Flow as the Mean Time To Resolution (MTTR) is reduced. On the contrary, if we standardized and enforced the use of a specific logging library that implements the standard we may increase flow (by saving teams time implementing their own) but we may also hinder product development and delivery of business value by not accommodating for edge cases in some teams implementation. In this case the minimum viable standard is to enforce the logging standard and not the implementation of a library.

Foundational systems are fundamental to increasing flow. They’re the equivalent to the machines and robotics in a manufacturing plant. Centralized teams that focus on building a platform to enable autonomous teams, sometimes called Platform Engineering teams, should focus relentlessly on a self-serve sub-system to enable teams to spin up and tear down their own systems in all environments. Providing a Platform-As-A-Service is one way to achieve this. Furthermore they should provide foundational tooling and systems that enable support of engineering teams to gain visibility and incident response. In doing so we can standardize on Incident Response (IR) and SRE processes if we all have a defined standard for logging, monitoring, metrics and alerting.

We can increase flow further beyond just standards definition. Take, for example, the new and much hyped world of “microservices”. How long does it take to stand up and deploy a new service/system in your organization? If there are manual steps or un-automated and repeatable steps that several teams are solving then perhaps we can build a generator that scaffolds a service for us, let’s say using Yeoman that bakes in a logging library, metrics library, service status and health endpoints etc. We can enable and encourage standardization and reduce the time it takes spin up services by investing in automation of repeatable tasks. Dr Eliyahu Goldratt, in his book “The Goal” calls this Theory Of Constraints. A process by which we map out processes or tasks, in this case the steps involved to stand up and deploy a service, and attribute time/cost to each step. In doing so we can identify the bottlenecks and remove them, in this example by automating them. This process is cyclical and theoretically is never finished.

A final example of increasing flow is a relentless focus on Developer Experience (DX). When onboarding a new team member, or encouraging other teams to contribute and send pull requests to our systems it’s essential that teams value and promote DX. By striving to reduce the time it takes to spin up and contribute to your systems you inadvertently encourage contribution. The aim here is again to increase flow by automating the setup process. If teams focus on DX as a first class citizen in software development then contributing to another teams system should be as little as one of two commands locally e.g. git clone [repo] and vagrant up.

Metrics that encourage Flow

So how do you encourage a focus on flow across the whole organization. There are three main components to this that I see. A company culture that values and embraces this way of working and is brave enough to step away from the old orthodoxy and challenge the current way of thinking. Secondly an organizational leadership and structure that enables this way of working, where teams are highly aligned and have common goals to drive the enablement of engineering teams and to achieve a healthy balance between alignment and autonomy. Finally, we can use some common metrics that encourage the behaviors that we want to see. Here are some examples of the “right” metrics to do so:

- Mean time to stand up (or delete) a service/system - From idea to production what are the steps required? How much is automated? What is the biggest bottleneck. For significant gains try embedding someone from Platform Engineering in teams and have them work together to encourage empathy and insight into the bottlenecks for shared gains.

- Mean Time To Resolution - How long does it take from incidents occurring until you have a resolution in front of a customer. Track these data points and focus relentlessly on them. After Action Reviews (aka Post Mortem's) are great times to discuss and record this. In doing so we encourage the behavior to increase flow and directly impact business and customer value.

- Cycle Time - This may be the time it takes from starting a work item through to it being in production and encourages fast feedback loops. This is usually easily automatable as much of this information can be extracted from an issue tracking or version control system. Plot it over time and include the discussion as a part of teams retrospectives.

- Work In Progress (WIP) Limits - Encourage teams to apply WIP to manage their queues. This encourages greater granularity and as a result increases faster feedback loops to eliminate waste.

These metrics can be recorded at the team level and aggregated across your engineering organization. Encourage teams to have sessions where they create Value Stream Maps for their pipeline and stick them on the walls in the office. Discuss them and your metrics regularly and drive improvements in flow relentlessly to reduce cost of delay and delivery customer value quicker.